Ajijic History

Ajijic history is rich in tradition and culture.

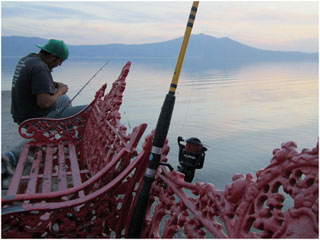

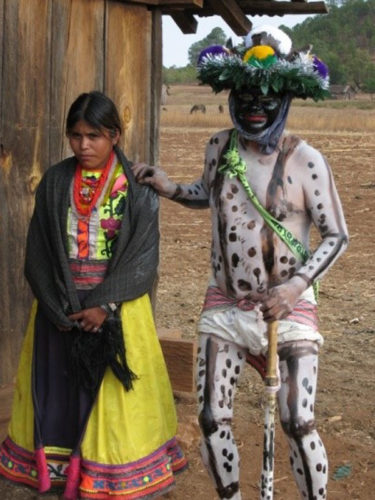

Nomadic people roamed throughout the lake region 10,000 to 12,000 years ago and recorded settlements occurred as early as 1300 A.D., when Nahua, Cora and Huichol people migrated here. Today, the Huichol Indians still inhabit the area and maintain their ancient Uto-Aztecan language along with their bright bead and textile arts. The name “Ajijic” or “Axixic” (both pronounced A-hee-heek) is a Nahua word meaning “the place where the water springs forth.” The ancient native people were a fishing culture, deriving their protein from the abundant species found in the lake.

In 1522, the Spaniards arrived in Ajijic, just after Hernan Cortes conquered Mexico. Having found paradise, they soon began establishing haciendas, planting corn and coffee and raising cattle, and fishing the lake, too. Franciscan Missionaries eventually arrived and gave Ajijic its patron saint, San Andreas, and began constructing the beautiful Iglesia de San Andreas, which sits just off the central plaza. You can still see the generations of construction in the church, from early 16th century all the way to modern-day improvements.

Ever since those early days, people from all over the world have been drawn to the area. But it wasn’t always easy to get here – modern roadways from Guadalajara to Chapala, which sits 11 kilometers east of Ajijic, were not built until the 1950s. Getting to Ajijic from there was either by boat or by donkey trail. Today the area boasts modern roadways, but not too modern.

Up until the arrival of the Spanish, the region was occupied by nomadic Indian tribes, probably the Cocas tribe that settled the northern shore. There seem to be many explanations, and meanings for the names Chapala and Ajijic, all of which are Indian place names, probably derived from Nahuatl, the native language of the area.

Ajijic’s population of 10,509 (2010 census) excludes the hundreds of visitors from Guadalajara (35 miles (56 km) north) who spend weekends and vacations there.

Many retired Americans and Canadians now live in Ajijic, about 1,000 full-time and another 700 during the winter months. As a result of these foreign residents and visitors, Ajijic has numerous art galleries, fashion and curio shops, as well as restaurants and bed and breakfast inns. The Lake Chapala Society on the grounds of the former estate of Neill James in central Ajijic has about 3,000 mostly foreign members.It serves as a focus of over 50 expat activities and services for the estimated 40,000 foreign residents who live around Lake Chapala. Mexico’s National Chili Cook-Off has been held in Ajijic since 1978 and currently attracts thousands of Mexican and International visitors each February.

Ajijic has attracted foreign artists and writers since the 1890s.Englishmen Nigel Millet and Peter Lilley settled in Ajijic before World War II and under the pen name of Dane Chandos wrote Village in the Sun (1945, G.P. Putnam’s Sons), about building a house on the edge of the lake in nearby San Antonio Tlayacapan. Using the same pen name, Peter Lilley later teamed up with Anthony Stansfeld (an English academic) to write House in the Sun (1949), which concerns the operation of a small inn in Ajijic. They were written when the main road was unpaved, ice was delivered by bus from Guadalajara, and electricity was just being installed.

ajijic was settled by people who came from the north.

Ajijic was settled by people who came from the north, and their origin is explained by a legend. There was a place far to the north called “Whiteness,” and, from its seven caves, seven tribes set out towards the south.

This migration probably took place in the second half of the 11th and the first half of the 12th centuries. The Nahuas were different from other Indian tribes around the lake. These primitives lived on Chapala’s vast shores with no thought of founding permanent pueblos. Nor were they curious about their own origins, their forefathers or their names.

Their vision of the world was simple. They were completely absorbed with the rendering of tribute to their gods. It was through, they thought, the pleasing of these deities that the sun shone and the rains fell on their land. Obtaining their daily sustenance was their primary reason for being.

Their second priority was defending themselves against hostile Tarascos and other neighboring tribes. To ward off such attacks, the Nahuas established complex barricades on the shores of this immense lake, a dwelling place of the goddess Machis.

In 1522, the Olid Expedition reached the eastern shores of Lake Chapala. When they arrived, Captain Avalos met with little resistance. A royal grant gave joint ownership of the area to Avalos and the Spanish Crown. Close in Avalos’ (a cousin of Cortez) wake came other relatives of Cortez. One, by the name of Saenz, acquired almost all of the property that is now Ajijic. By 1530, the Saenz property was one big hacienda. The principal crop was mezcal for making tequila. The hillsides were covered with mezcal plants and their soft blue-green blanketed hill and dale.Coffee and corn were planted. When a tequila distillery was introduced, the product was exported to Spain along with the coffee beans. A “molino” (mill) was established, which Saenz built on the site of the present-day Old Posada. The blast of a conch horn at 4:00 a.m. called the Indians to bring their corn to the mill to be ground. This mill remained in business until the 1940’s. It is still intact atop the Posada today.

Later, Franciscan missionaries visited the village and gave it a patron saint, San Andres (Saint Andrew). Royal land grants included the Indians who lived there. Franciscan Fray Sebastian de Parrago introduced the first oranges to Ajijic in 1562. Henceforth, the village was called “San Andres de Axixic.” Its cobblestone streets laid down during the days of Spanish rule are still used today.

After the border wars (1910-29), the Saenz hacienda was split into many small holdings and all Mezcal cultivation ceased, as each Mezcal plant needs seven years to mature and only large estates can devote such acreage solely to growing plants.

During the Porfirian Era (1875-1910), Ajijic was isolated from Chapala by land. Their commerce with the resort town of Chapala, which was five miles away, was confined to an occasional cargo canoe touching down at the Saenz Hacienda for a load of tequila or coffee beans.

In the early 1920’s, Mr. Ramirez, Mayor of Chapala, purchased the Saenz Hacienda. He re-named it Hacienda Tlacuache (The Opossum). The property is still owned by the Ramirez family and has, over the years, been sublet to various people.

In 1925, Ajijic was discovered by European intellectuals and became a refuge for those fleeing political persecution after World War I. Louisa Heuer, a writer, and her brother Paul, were German refugees. They owned Casa Particular—a small inn overlooking the lake. Zara Alexeyewa, the great-granddaughter of Gideon Wells, Secretary of the Navy under President Abraham Lincoln—first came to Guadalajara in 1925 to dance at the Teatro Degollado. She was accompanied by her mother and adopted brother, Holger Mehner.

The trio had just finished a tour of Europe and South America where Zara and Holger had introduced ballet to that continent. Zara, enchanted with Lake Chapala, moved her menage to Ajijic. They lived in a rambling, decaying, old house on the edge of the lake, next to the Heuers.

Herbert and Georgette Johnson, English refugees from France, comprised the remaining foreign family residing in Ajijic in the 1930’s. The Johnsons built a house, set in an English garden that overlooked the lake.

Nigel Stensbury Millett, the British author, arrived in Ajijic with his father in 1937. They first lived in Casa Particular with the Heuers. Later they moved to Hacienda El Tlacuache where Nigel quickly became part of the Ramirez family. Millet induced Mayor Ramirez to change the name of his hacienda to Posada Ajijic. A few rooms and a bar were added and under Millet’s management, an inn was born. The Posada Ajijic remains today, a lakeside landmark. From 1975 until the early ‘90s when they built their own establishment, Judy and Morley Eager owned and operated the Posada Ajijic.

In the mid-30s, three engineers, their curiosity aroused as to why a certain red hill (variously called Bald Mountain, Gold Mountain, or simply Quarry) was without growth when all others in the area were wooded, discovered gold in the hill.

Almost overnight the gold rush was on. Corn mills were transformed into gold mines. The women of the village reverted to hand-operated metates to pulverize corn for family tortillas. Farmers left their fields, fishermen dropped their nets, and trouble beset Ajijic as food became scarce. Neighbors quarreled. Murders and mayhem were rife.

Leaders in the gold rush were the ballet dancers, Zara and Holger, for they owned the best mine. Zara found life as a dancer tame, compared with gold mining. Armed with her “treasure finder,” Zara looked for gold, but found only trouble. One associate after another cheated her. The dream of gold began to fade.

There was gold in the hills, but not in sufficient quantity. The gold fever cooled. Men returned to their tiendas. Gold mills went back to grinding corn. Fishermen spread their nets again, and farmers re-plowed their land. The Ajijic gold rush had ended.

Once again the village settled back among the green-bladed mango trees squeezed in between mountains and lake. Only two new houses, one built by a Mexican colonel, the other by the English couple, broke the natural curve of grassy shores. Only the unfinished tower of the church, jutting above the tree tops, could be seen by approaching boats.

While living at the Old Posada, Nigel Millett wrote the award-winning Village in the Sun, in collaboration with another Englishman, Peter Lilley. The book was published under their pen-name of “Dane Chandos.” Millett died in 1946 and is buried in the western part of the Ajijic cemetery, alongside his father. Peter Lilley lived in the house he and Millett had built in the village of San Antonio for many years after Millett’s death. It was there that Lilley wrote House in the Sun, which was also published under the name of Dane Chandos.

At this time, the road between Chapala and Ajijic was almost impassable. There were four bridges to cross and all of them had wide, gaping holes. Most cars made a detour, sliding down a steep, slippery bank to ford a stony torrent. Then the car was coaxed up the bank on the other side. This road continued on to Jocotepec, sometimes running along the beach, sometimes alongside the mountain.

Ajijic could scarcely be seen from the road. The houses, with their tiled roofs, grew out of the ground with their adobe walls and were hidden in a tangle of vegetation. The orderly rows of mezcal plants were gone. The narrow belt of land the village stood on was as thickly green as a cabbage patch—and every little bay was different. One was rocky, another sandy, and a third, reclaimed by the Indios as the lake went down, was planted in chili or peanuts right down to the water’s edge.

“Come to Ajijic and discover it’s history.”

Events and Holidays

February 5th - Constitution Day

Benito Juárez Birthday - 3rd Monday in March

Labor Day - May 1

Independence Day - September 16

Mother's Day - May 10th

Day of the Dead - November 2

Revolution Day - the third Monday in

November

November 12th - Day of the Virgin of Guadalupe Christmas Day - December 25